Henry Moore Artwork Catalogue

2014-16 Leeds Art Gallery Collection Display, Figure and Architecture: Henry Moore in the 1950s

2014-16 Leeds Art Gallery Collection Display, Figure and Architecture: Henry Moore in the 1950s

'I think architecture is the poorer for the absence of sculpture and I also think that the sculptor, by not collaborating with the architect, misses opportunities of his work being used socially and being seen by a wider public ... the time is coming for architects and sculptors to work together again.'

From Sculpture in the Open Air: A Talk by Henry Moore on his Sculpture and its Placing in Open-Air Sites, 1955

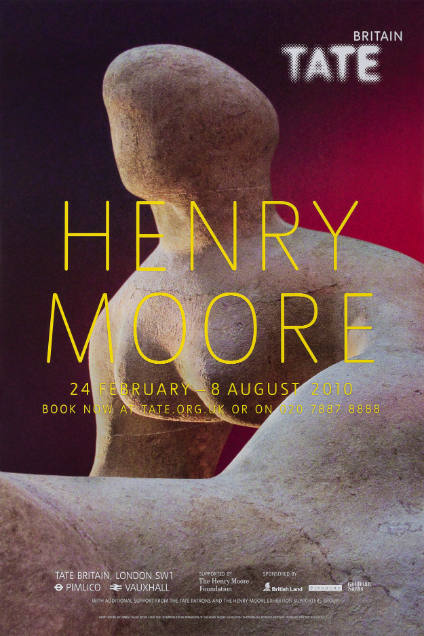

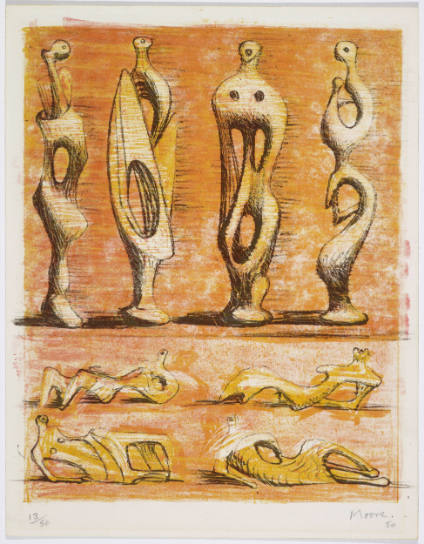

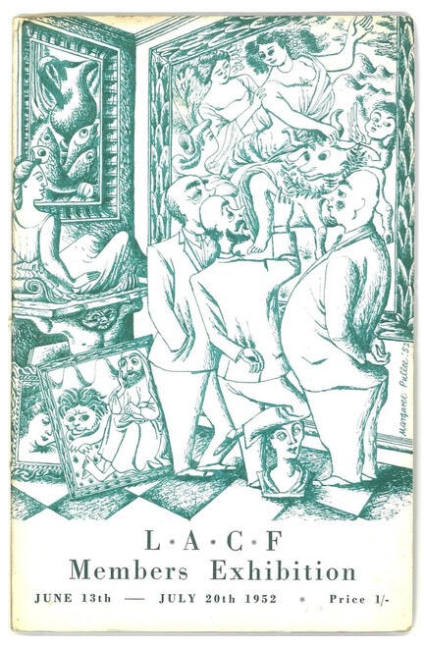

Figure and Architecture: Henry Moore in the 1950s is a display of sculpture, photographs and archive material from the collections of The Henry Moore Foundation and Leeds Museums and Galleries relating to three key architectural commissions undertaken by Henry Moore: the 'Time Life Screen' (1952-53), the unrealised designs for the English Electric Company (1954) and the 'UNESCO Reclining Figure' (1957-58).

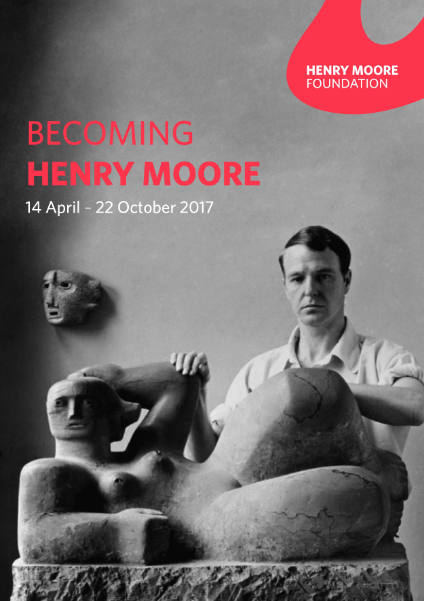

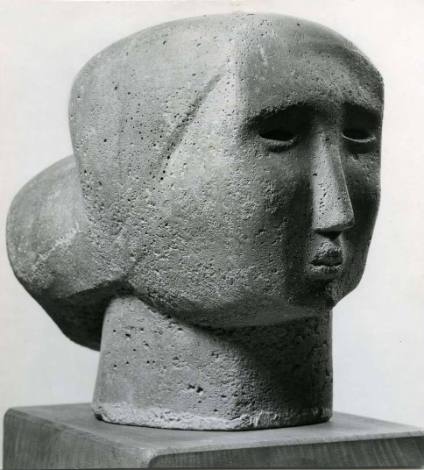

Throughout the 1950s Moore received an increasing number of approaches from architects wishing to commission sculpture for new buildings and public spaces. The universal, humanist themes of his work and his international reputation as a leading modern sculptor were considered particularly apposite for the reconstruction and civic regeneration projects of the post-war period. Yet, despite his belief in the potential for both artist and architect, Moore was initially reluctant to accept such commissions. He expressed concern that sculpture was too often considered by architects as 'mere surface decoration', while the increasing tendency for invitations to make work in urban sites was deeply at odds with his preference for natural, landscape settings, which he felt enhanced the inherently human, organic forms of his sculpture.

The Time Life Screen and English Electric Company maquettes were commissioned by Austrian architect Michael Rosenauer, in whom Moore found a collaborator willing to incorporate sculpture into the design of the building. These projects represent Moore's most fully realised attempts to integrate sculpture into the rhythm and fabric of a building by introducing abstract and biomorphic forms into the restrained elements of modern architecture.

The commission of a sculpture for the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) headquarters encapsulated the challenge Moore found in reconciling his asymmetrical, human forms with stark, geometric architectural planes. The project provided the impetus for numerous maquettes positioning figures on steps, platforms, benches and against walls; these architectural elements are integral to the sculpture, mediating between figure and built environment. The final sculpture would appear against a backdrop of the new building's rectilinear, glass façade. This prolific period of experimentation provided ideas that Moore would continue to refer back to throughout his career.