Henry Moore Artwork Catalogue

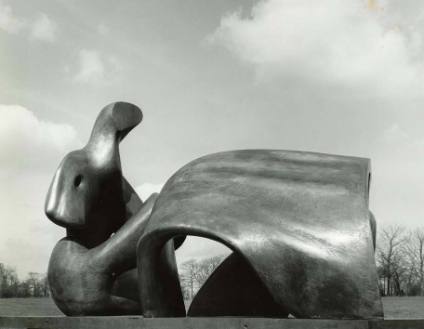

Three Piece Reclining Figure: Draped

Three Piece Reclining Figure: Draped

stamped Moore, 0/7

The

three elements of this late, monumental, reclining figure incorporate smooth

and curvaceous passages which are sharply cut into stump-like forms. The

largest part, a rising chest and neck, juxtaposes one amputated arm with a

heavily bowed and bulbous counterpart which merges with the torso. The torso

juts up and outwards towards the centre of the composition before being bluntly

severed. This treatment is echoed in the head, resulting in a blank facial

plane. The verticality of this element contrasts with the horizontal arched

‘skirt’ of the figure, which shields a separate and more sinuous ‘leg-form’.

The component parts are carefully spaced across the flat bronze base.

Moore

had been preoccupied with the idea of breaking the reclining figure into

multiple parts since the 1930s. Early explorations include Composition (LH 140) and Four-Piece

Composition: Reclining Figure (LH 154), both of 1934. These highly

abstracted figures allude to Moore’s involvement with surrealism and geometric

abstraction. Despite the apparent conflict between these two trends in

contemporary art, Moore incorporated aspects of both in his work.

The

arrangement of multiple sculptural elements across a flat surface also points

to the influence of Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966) and Jean Arp (1886-1966).

Moore understood that perceptual unity did not require physical continuity, and

he could therefore explode the figure into several parts. In ‘reconstructing’

it, the viewer – unable to see all elements at once - would need to move around

the work. Changes in their angle of vision would create an infinite number of

views and therefore no fixed meaning or single comprehension of the whole.

These qualities were considered in line with surrealist thinking.[1]

However, in contrast to the surrealist tendency toward the irrational or subconscious, Moore’s multi-part figures are highly conceived and controlled creations. His understanding of spatial arrangement aligned him with artists such as Ben Nicholson, who promoted a formal, non-objective abstraction. The interdependence of space and form was further explored by Moore in his stringed sculptures later in the 1930s, and in his Helmet Heads and related works investigating the interplay of internal and external forms.

Moore’s

profound understanding of the human body allowed him to experiment with

breaking it apart. In Three Piece

Reclining Figure: Draped the space between the forms is of crucial

importance. Moore commented:

‘You know how sometimes in a museum they will

reconstruct an animal, and they put a piece of knee, and then they will leave a

blank with just a bit of armature, and then they put the foot. Now, the

distance that they make the knee from the foot is terribly important… Now the

same thing applies in these two-piece and three-piece sculptures. The space

between those pieces is just as important, and if somebody put them together in

the wrong way it would be for me as wrong as if somebody put a knee and a foot

too close together.’[2]

Moore’s

fragmented figures of the 1930s, seen by some as a deformation of the human

body, were followed by works with a greater degree of humanism in the 1940s and

1950s. In 1959, when he returned to the subject of multi-part figures,[3]

the component parts are clearly related to landscape and geological structures.

Three Piece Reclining Figure Draped,

however, is not boulder-like or evocative of nature; it is carefully considered

and arcane. Completed when Moore was 77, the sculpture shows him re-engaging

with some of his earliest, most daring, abstract tendencies. The work cleverly

combines the shifting comprehension and activation of sculpture beloved by the

surrealists, and the command of formal relationships essential to geometric

abstraction.

[1] For Moore’s use of interdependent space and form in his figures see Rudolf Arnheim ‘The Holes of Henry Moore: On the Function of Space in Sculpture’ in The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 7, No. 1 (Sept. 1948), pp. 29-38. For Moore and surrealism see Michael Remy, Surrealism in Britain, Aldershot,1999, p. 133.

[2] Moore in The Donald Carroll Interviews, 1973, pp. 49–50, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore: Writings and Conversations, Lund Humphries, Aldershot, 2002, pp. 289.

[3] The first of these is Two Piece Reclining Figure No. 1 1959, LH 457.