Henry Moore Artwork Catalogue

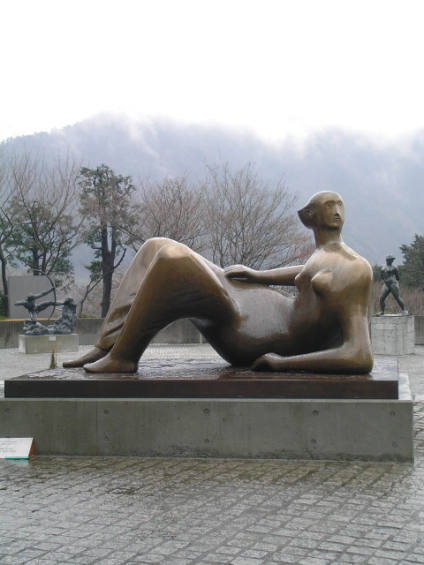

Reclining Figure: Angles

Reclining Figure: Angles

stamped Moore, 0/9

Like

many of Moore’s late works, Reclining

Figure: Angles is characterised by a sense of confidence and consolidation.

The work pulls together diverse interests from his long career, and combines

them with a distinctive twist typical of works from

this period. [1] Alan G. Wilkinson, The Drawings of Henry Moore, Tate Gallery, London/Art Gallery of

Ontario, Toronto, 1977, reprinted in Alan Wilkinson (ed.), Henry Moore:

Writings and Conversations, Lund Humphries, Aldershot, 2002, p. 98. [2] Henry Moore quoted in J.D. Morse,

'Henry Moore Comes to America', Magazine

of Art, Vol.40, No.3, Washington DC 1947, pp. 97-101. [3] Henry

Moore quoted in Sculpture in the Open Air: A Talk by Henry Moore on his

Sculpture and its Placing in Open-Air Sites, edited by

Robert Melville and recorded by the British Council 1955; typescript copy in

The Henry Moore Foundation Archive, Perry Green. [4] Ibid.

The

figure’s pose has echoes of the Mesoamerican chacmool sculptures that sparked

Moore’s interest in the reclining figure. Like the chacmool, the figure

reclines on its back, supported on its elbows with its knees raised and head

turned away from the body. The combination of ‘stillness and alertness’[1] that

Moore so admired in the chacmool is also characteristic of his reclining

figures. Unlike traditional European depictions of reclining female figures,

which are usually in passive repose on their sides, Moore’s female subjects are

active, propping themselves up and gazing intently outwards. Moore’s early

interest in the reclining figure theme was in part due to practical

considerations related to working in stone; a standing figure in stone would be

weak at the ankles, whereas a reclining figure – which can recline on any

surface - is well supported and stable.[2] He

swiftly discovered, however, that the tensions,

oppositions and asymmetry of the reclining figure made it an ideal subject for

endless variations in form, and it became an obsession that he explored

throughout his career.

References

to classical sculpture are also apparent in the naturalism of the figure and

the drapery covering her lower portion. In the early part of his career, Moore

rejected classical sculpture but following his first visit to Greece in 1951 he

began incorporating drapery in his sculpture. He observed that drapery could

emphasise the tension in a figure, ‘for where the form pushes outwards, such as

on the shoulders, the thighs, the breasts, etc., it can be pulled tight across

the form (almost like a bandage), and by contrast with the crumped slackness of

the drapery which lies between the salient points, the pressure from inside is

intensified.’[3] The drapery

in Reclining Figure: Angles, minimally

rendered in large, soft creases, serves to amplify the sharp angularity of her

knees.

Reclining Figure:

Angles also

demonstrates Moore’s enduring interest in analogies between the reclining

figure and landscape. The undulating curves of the female form echo the forms

and rhythms of landscape, bringing to mind not only

the hills and dales of Moore's Yorkshire childhood, but also the rolling

countryside surrounding his home at Perry Green. Moore also saw a correspondence

between the folds in drapery and mountains, which he described as ‘the

crinkled skin of the earth.’[4]

The work’s subtitle calls attention to its most

distinctive characteristics. Unlike the chacmool, whose pose is symmetrical

apart from the head, Reclining Figure:

Angles is a mass of asymmetric forms and tensions. Her head is turned

sharply towards the elongated expanse of her left shoulder, which juts out

above a right-angled arm, visibly taking the strain of her massive torso. Her

right shoulder is pulled back, raising her other arm up, horizontal to the

ground. Her knees project up and out, the opposing forces between them made

visible in the drapery. Further angles are introduced in her feet, breasts,

nose and hair. Moore was 81 when he completed Reclining Figure: Angles, but there is a playfulness in her

angularity, as if the artist was setting himself a challenge. Although her

angles are as numerous and diverse as her influences, Moore reconciles them in

a rhythmic harmony than runs through the length of the figure.