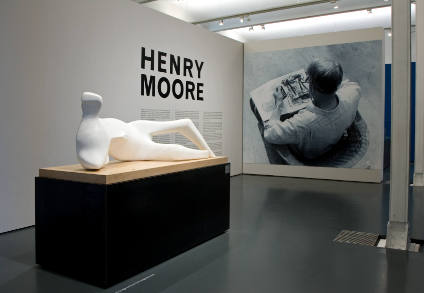

Henry Moore Artwork Catalogue

2006-07 Rotterdam,Kunsthal, Henry Moore: Sculptuur en architectuur

Skip to main contentMore Information

2006-07 Rotterdam,Kunsthal, Henry Moore: Sculptuur en architectuur

14 October 2006 - 29 January 2007

Henry Moore Sculptuur en Architectuur explores the ways in which Moore attempted to reconcile his interest in nature with the knowledge that increasingly his works were finding homes in an urban environment. Throughout his life Moore pronounced that he was not interested in working with architects, as too often public sculpture was considered only as an afterthought, as mere surface decoration. Yet at the same time, he continued to work with architects throughout his career. This exhibition addresses these conflicts and examines how the artist explored the fundamental relationship between figure and architecture in both his drawings and sculpture.

The exhibition encompasses five areas. The first considers Moore’s West Wind carving for Charles Holden’s London Transport Headquarters in 1928. Moore carved this at the same time as his reliefs for garden benches which have been restored and exhibited here for the first time. Moore’s abandoned project for reliefs on Holden’s Senate House are also considered; the uncarved blocks of stone cut to Moore’s specifications still remain in position at the University of London today. This section further explores Moore’s relationship in the 1930s with both the Surrealists and the Constructivists, and with international architects residing in London during the 1930s including Marcel Breuer, Serge Chermayeff, Wells Coates, Walter Gropius and Berthold Lubetkin.

The second section examines Moore’s collaboration with Michael Rosenauer for the Time/Life Building on Bond Street and studies for Rosenauers’s unrealised English Electric Company Headquarters. These were efforts to unify a vision of both architect and artist in a complete concept for the building. These sculptural forms anticipate Moore’s Bouwcentrum wall in Rotterdam, the subject of section three, in which the building’s brick faÁade consists of both industrial and organic forms merging into and projecting from the wall. Related bronze wall reliefs and archival material showing the wall under construction are included.

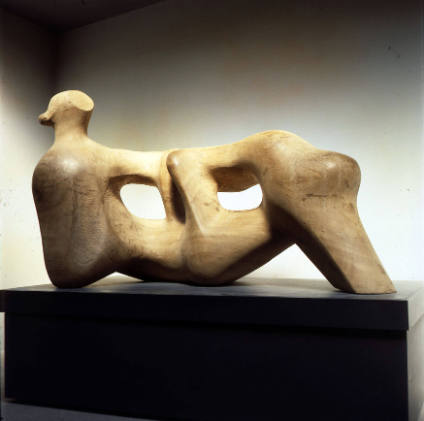

Part four concentrates on Moore’s attempts to reconcile the human form with architecture with the UNESCO Reclining Figure and related experimental sculptures exploring the positioning of figures with architectural elements such as steps, benches or walls. These had varying degrees of success. With Wall: Background for Sculpture, Moore tried a variety of ideas in front of the walled background only to find that in every case they worked better without the architectural background. This section also includes a number of the artist’s photographic collages that have never been exhibited before, revealing how his sculptural experiments with architecture were closely tied into his production of lithographs.

Finally, the exhibition will look at Moore’s determination to have architects such as IM Pei, with whom he collaborated on four projects, consider possible works for commissions from already existing maquettes. Moore was able to retain creative control without having to take into account the restrictions of a potential environment while developing a sculptural idea. He thus worked in a completely antithetical position to that of many contemporary public sculptors, in that the majority of his work was inherently not site-specific. This enabled Moore’s public sculpture to be associated with, yet independent from architecture, and works such as Mirror Knife Edge for the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC or Large Figure in a Shelter can be seen in this context. They are tough bold forms that hold their own, independent of their environment, and often take on architectural qualities in themselves.

The exhibition encompasses five areas. The first considers Moore’s West Wind carving for Charles Holden’s London Transport Headquarters in 1928. Moore carved this at the same time as his reliefs for garden benches which have been restored and exhibited here for the first time. Moore’s abandoned project for reliefs on Holden’s Senate House are also considered; the uncarved blocks of stone cut to Moore’s specifications still remain in position at the University of London today. This section further explores Moore’s relationship in the 1930s with both the Surrealists and the Constructivists, and with international architects residing in London during the 1930s including Marcel Breuer, Serge Chermayeff, Wells Coates, Walter Gropius and Berthold Lubetkin.

The second section examines Moore’s collaboration with Michael Rosenauer for the Time/Life Building on Bond Street and studies for Rosenauers’s unrealised English Electric Company Headquarters. These were efforts to unify a vision of both architect and artist in a complete concept for the building. These sculptural forms anticipate Moore’s Bouwcentrum wall in Rotterdam, the subject of section three, in which the building’s brick faÁade consists of both industrial and organic forms merging into and projecting from the wall. Related bronze wall reliefs and archival material showing the wall under construction are included.

Part four concentrates on Moore’s attempts to reconcile the human form with architecture with the UNESCO Reclining Figure and related experimental sculptures exploring the positioning of figures with architectural elements such as steps, benches or walls. These had varying degrees of success. With Wall: Background for Sculpture, Moore tried a variety of ideas in front of the walled background only to find that in every case they worked better without the architectural background. This section also includes a number of the artist’s photographic collages that have never been exhibited before, revealing how his sculptural experiments with architecture were closely tied into his production of lithographs.

Finally, the exhibition will look at Moore’s determination to have architects such as IM Pei, with whom he collaborated on four projects, consider possible works for commissions from already existing maquettes. Moore was able to retain creative control without having to take into account the restrictions of a potential environment while developing a sculptural idea. He thus worked in a completely antithetical position to that of many contemporary public sculptors, in that the majority of his work was inherently not site-specific. This enabled Moore’s public sculpture to be associated with, yet independent from architecture, and works such as Mirror Knife Edge for the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC or Large Figure in a Shelter can be seen in this context. They are tough bold forms that hold their own, independent of their environment, and often take on architectural qualities in themselves.

19 July 2006 - 29 October 2006

16 December 2022 - 26 August 2023

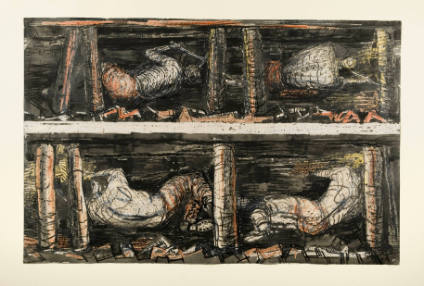

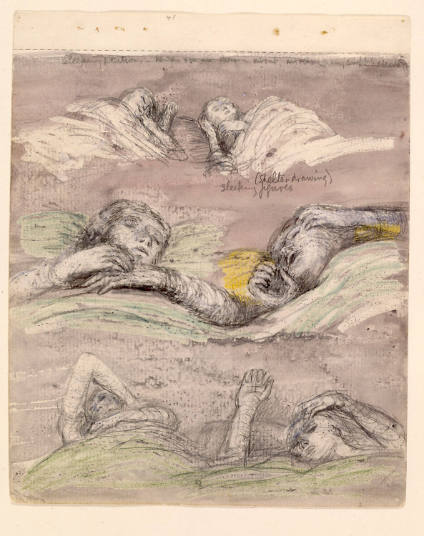

Drawing in the Dark is the largest exhibition to date of Moore’s coalmining drawings, completed in 1942 for the War Artists’ Advisory Committee. When Moore was asked to record the coalminers working to power wartime Britain, he chose to visit the mine his father had worked in, Wheldale Colliery in Castleford, where he spent a week drawing from observation. Subsequently, he worked from memory to create the remaining drawings which were all completed within six months. This fascinating body of work reveals the back-breaking labour endured by nearly 3/4 million miners as they made their vital contribution to Britain's war effort, while also providing new insights into Moore’s life and artistic process.

01 April 2022 - 30 October 2022

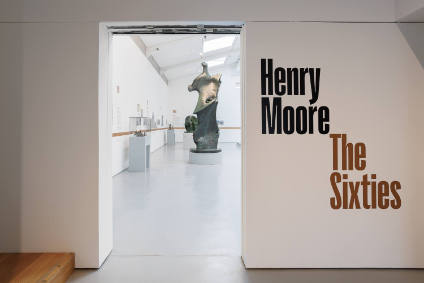

Henry Moore: The Sixties presents a fascinating insight into Moore’s life and work during this pivotal decade in his career. The exhibition reveals the dramatic shift in his working practices that enabled him to work on an increasingly monumental scale; his move towards greater abstraction; and the enormous global demand for his work during this period, along with the controversy this generated. The exhibition feautures sculptures, drawings, graphics and archive material drawn entirely from the Henry Moore Foundation’s collection.

01 April 2001 - 30 September 2002

29 March - 29 August 2010 (Perry Green), 3 February - 3 April 2011 (Leeds)