Henry Moore Artwork Catalogue

Woman

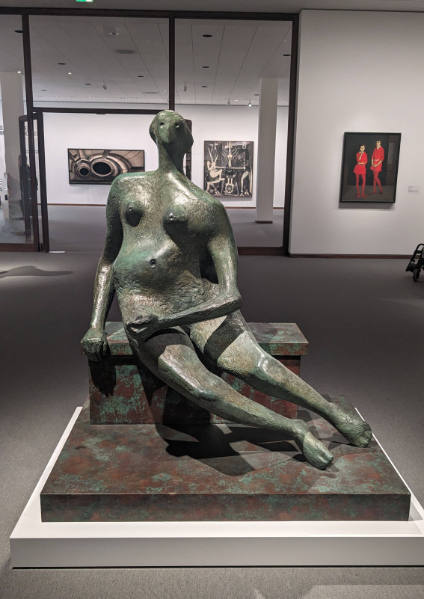

Woman

| The reclining figure theme

was arguably Moore’s fundamental artistic obsession, but he also made

repeated explorations of the seated figure during the 1950s. Moore said that

between the reclining and seated figure, ‘there are enough variations to

occupy any sculptor for a lifetime. In fact if I were told that from now on I

should have stone only for seated figures I should not mind it at all.’[1]

Woman, with her exaggerated

roundness and fullness of form, can also be seen as an inventive variation on

another of Moore’s great obsessions: the mother and child. In many works he

explored the sculptural relationship between two forms, one small and one

large, but he was also fascinated by the theme on a human level, and how it

had inspired some of the earliest known sculptures.[2]

Here, he presents a mother-to-be, her life-giving potential on display in the

form of a rounded belly projecting from an otherwise concave torso.

In 1926, Moore made a series of sketches of prehistoric sculptures and rock drawings from reproductions in Herbert Kuhn’s Die Kunst der Primitiven, published in 1923. Three pages of sketches reveal a particular fascination with a small Palaeolithic sculpture, then known as the Venus of Grimaldi.[3] Although these studies did not have an immediate impact on his sculpture, Woman – made some thirty years later – bears striking formal and symbolic similarities with the ancient figure. Both sculptures depict an armless woman with truncated legs, swollen stomach and large breasts. Both have been interpreted as powerful images of fertility. Although Woman has her roots in the ancient past, Moore’s distinctive treatment of the subject confirms that we are seeing a twentieth century interpretation of this universal theme. Her head, unlike those of her prehistoric forebears, has been reduced in size to ‘emphasise the massiveness of the body’, as Moore put it, and has not been overlooked in terms of detail.[4] A nose, eyes and hair lend the figure a sense of poise and refinement that is further emphasised by the angle of the head which leans back slightly, drawing the chest up. During this period, Moore often used drapery to draw attention to particular aspects of the human form and highlight the tension in a pose. Although Woman is unclothed, her skin is used to similar effect. The monumental breasts and rounded torso appear to push outwards, the skin stretched to the point of smoothness between salient points. Simple, circular incisions denote nipples and a navel, further emphasising these features. The amputated limbs of Woman recall a male seated figure that Moore made just a few years earlier in 1953-54, titled Warrior with Shield (LH 360). Made in the aftermath of the Second World War, the warrior’s mutilated body speaks to the tragedy of war. In contrast, the subject of Woman does not seem reduced by trauma.[5] Instead, the roughly textured sockets which mark the sites of her lost arms suggest slow, archaeological decay. Her essence, however, and the potent forms of breast and abdomen, seem |

[1] John D. Morse, ‘Henry Moore Comes to America’, Magazine of Art, New York, March 1947, pp. 100-1.

[2] Henry Moore cited in John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London, 1968, p. 61.

[3] These sketches were made in Notebook No.6 (SKB 9) and are all titled Study after ‘Venus of Grimaldi’. They are catalogued as: HMF 459 verso, HMF 460 and HMF 461; The Venus of Grimaldi subsequently became known as the Venus of Menton. It remains in the collection of the Musée d'Archéologie nationale et Domaine national de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France.

[4] Henry Moore cited in John Hedgecoe (ed.), Henry Moore, London, 1968, p. 326.

[5] Alice Correia, ‘Woman 1957–8, cast date unknown by Henry Moore OM, CH’, catalogue entry, December 2013, in Henry Moore: Sculptural Process and Public Identity, Tate Research Publication, 2015, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/research-publications/henry-moore/henry-moore-om-ch-woman-r1172100, accessed 26 May 2020.